Yameii Online, “Baby My Phone” (2021)

Greta Gerwig’s Barbie is now the highest-grossing domestic release in Warner Bros. history, overthrowing Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight released in 2008. It seems like everyday a new IP-based film is being announced, each source of material making less sense than the one before from Barney to Hot Wheels to…Pop-Tarts?

We can pull this thread even more, from Adam Mastroianni:

“Until the year 2000, about 25% of top-grossing movies were prequels, sequels, spinoffs, remakes, reboots, or cinematic universe expansions. Since 2010, it’s been over 50% every year.” Last year, the top ten highest-grossing movies were all reboots or sequels.

Tempting explanations for today’s apparent lack of original media are to point fingers at corporations for chasing greed or at audiences for being complacent in a decline in creativity. These explanations can both be somewhat true, but I’m more interested in exploring in the abstract how we got here and to answer a more existential question: Is culture dead? *vaguely handwaves* “it’s more nuanced than that”

To understand how we arrived at the current state of pop culture, it’s worth examining cultural trends of the past. It’s difficult to trace the exact origin of a culture, but a few recurring themes emerge:

1v1 Opposition

New subcultures historically appear in direct opposition to a dominant culture. Teddy Boys and Skinheads in the UK. Hippies and Bikers in the US. It also helps explain why youth drive culture and trends. Kids vs adults is an opposition as old as time. No one feels more helplessly alienated and misunderstood than a young person.

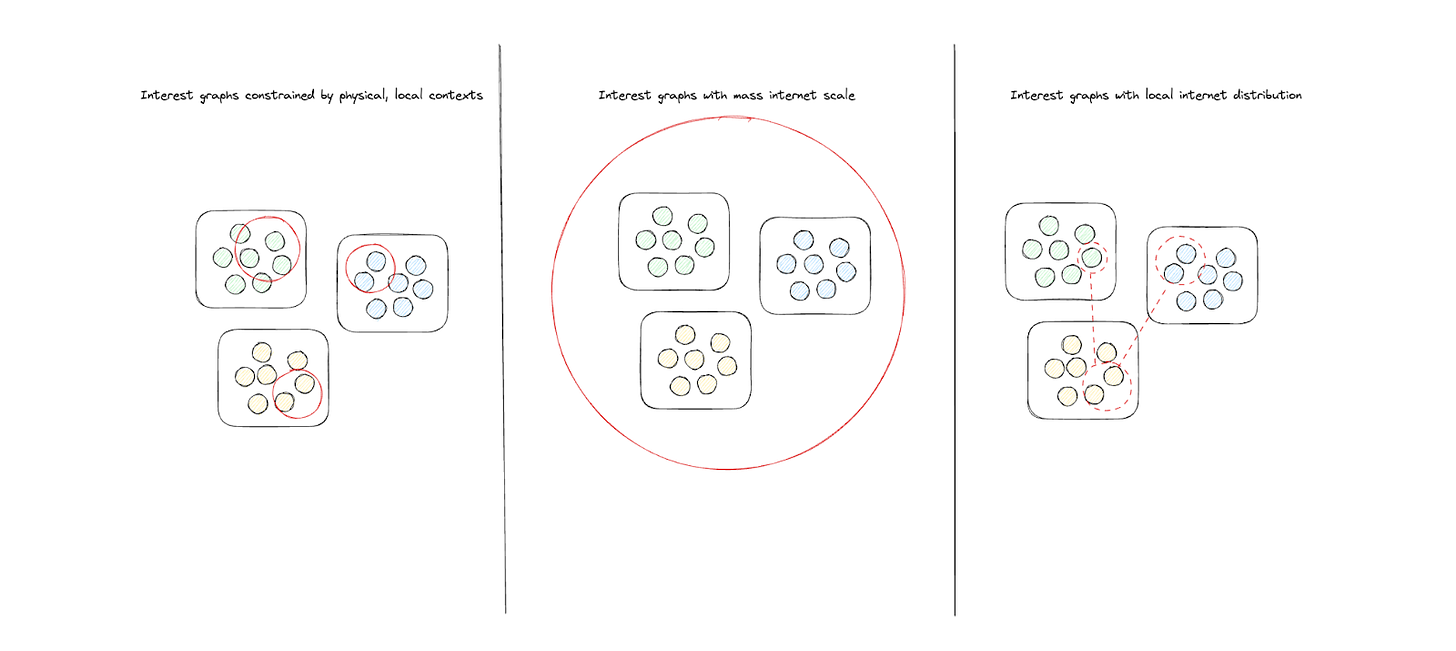

Local contexts

New cultures are best cultivated in intimate communities with rich context, often bonding around feelings of alienation and opposition as mentioned earlier. Chinese immigrants in San Francisco in the late 1800s created the signature style of Chinatown. Black and Latinx youth in the Bronx in the 1970s created hip hop. Both these subcultures, started by minority communities, are now mainstays of modern American culture.

Turning back to Barbie and the reboot paradigm. Both signals I’ve identified as precursors to subculture development—1v1 opposition and local context—have been wildly disrupted by the internet, irrevocably altering the way culture emerges and is ultimately produced.

1v1 Opposition → Omnivorism

While subcultures surface in opposition to some dominant culture, identifying any single, dominant culture today is nearly impossible.

Is anything “canon” anymore? Not really.

The internet allows unlimited amounts of information to proliferate at such lightning speeds that the notion of a stable canon becomes a bit absurd. Instead, we have omnivorous taste where objective taste does not exist and every “niche” interest can be somewhat commonplace.

Omnivorous taste is democratic in theory, but becomes messy in practice. If you can’t rally a passionate community around a strong message because there is no direct opponent and/or because you are competing with millions of other equally accessible concepts, it’s extremely difficult to gather any attention at all. In the end, people tend to default to a lowest common denominator (often monetary), ossifying monoculture.

From W. David Marx in Status and Culture:

Local Contexts → Mass Scale

Another example of why youth drive culture: they spend a lot of time together in close-quarters—in schools, sports teams, cultural groups, etc. Physical environments will always be an epicenter of community-building because there is more obvious, shared context. Take Atlanta rap culture as an example.

From Pierre “P” Thomas, CEO and Co-Founder of Quality Control Music, the label home to Atlanta-native artists like Migos, Lil Baby, City Girls, and Lil Yachty:

“Other labels have these A&Rs and CEOs and chairmen, sitting in an office looking on the internet at numbers on SoundCloud and Spotify—they’re just into the analytics. That’s part of it. But if I’m being honest—and it might sound ignorant—I don’t own a computer. I’m really out here in it.”

While the internet turbo boosts communities to reach mass scale, scale is a double-edged sword. You are able to reach more people in volume and thereby likely to reach more people who share certain interests, but it’s much harder to share context around language, physicality, etc. The result is often some form of dilution and context collapse.

Kieran Press-Reynolds writes about this dynamic in music. He unpacks how streaming platforms and major labels often slap labels on underground music genres in order to make them legible to mass audiences:

“Music genres, like anything mediated through language, are composite signifiers carrying a multitude of meanings for different people. [...] It’s practically impossible to grasp a music genre or scene in its totality, aware of every manifestation and influence, but you can dig deep in the ground and turn over as many rocks as possible. What playlists do is rub sandpaper over a music scene so there’s no dimensionality left (just a top-down list, usually organized with new popular songs near the top) and no timestamps (there’s no archive for what the playlist looked like before).”

So what does this all mean for culture exactly?

Pop culture today submits to power law-like distribution. Attention consolidates around a few mega stars/trends like Beyoncé or Taylor Swift (whose careers took off pre-Youtube) and bottoms out drastically. In a power law-like paradigm, there’s two (not ideal) ways to break through for commercial success:

Go for the head. Obviously if attention converges around a head, you should build around it—mega stars, established IP, etc. What I find unique today though, is that revival IP today pulls from troves of 20+ year old material, which poses questions around where the cultural “head” even exists.

Optimize for virality. Niche stars can still break through, but breakout moments happen more unpredictably than ever before, often driven by luck and virality. The concept of virality brings to mind images of TikTok and rags-to-riches stardom, but it’s also impacting how big budget media is produced.

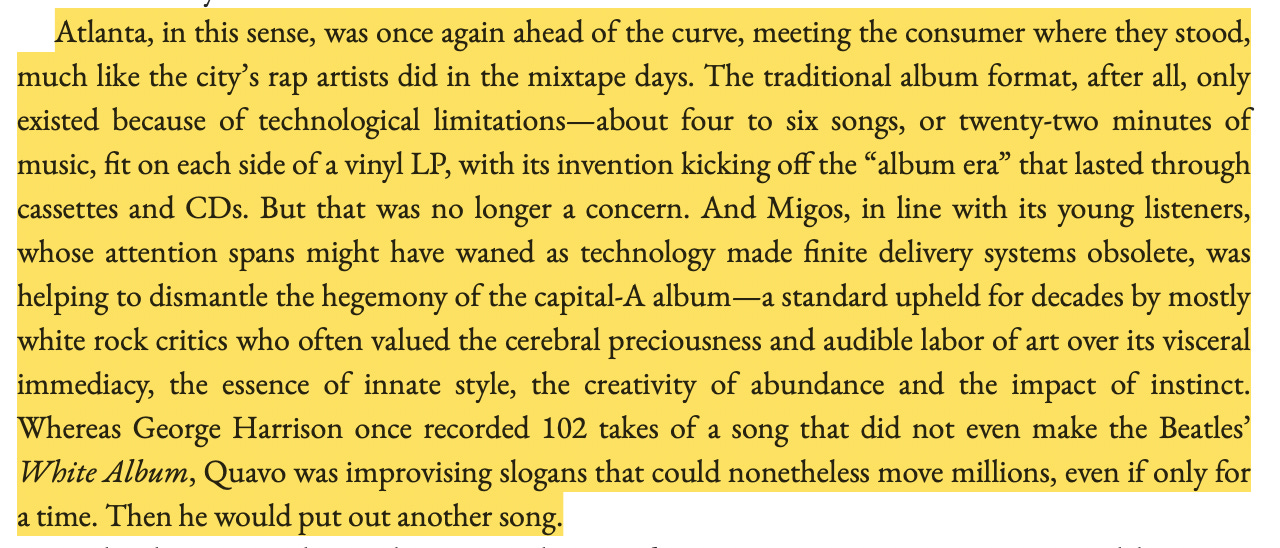

Take, for example, the music album. The album as we know it is dead. While albums used to be singular projects with clear narrative arcs, new albums are more often collections of disparate singles with banger potential or they’re shorter EPs. Artists are even teasing songs on TikTok to see which ones are worth releasing. A group who noticed and capitalized on this early was Migos in the mid 2010s (RIP Takeoff).

From Joe Coscarelli in Rap Capital:

The eventual result of a power law-driven landscape is a culture that prizes media that 1) fundamentally sits at the lowest common denominator such as behemoth corporations that own decades-old IP or 2) churns out high volumes of micro-content engineered to catch viral lightning in a bottle.

Despite all this, culture is far from dead—a new era is rapidly emerging.

In the absence of any singular enemy, omnivorism becomes the opponent. Subcultures have become more local, more niche, and more extreme, using internet tools for distribution. Regional rap continues to thrive, leaving digital trails on YouTube and SoundCloud. Teens seek community in extremely niche political Instagram pages.

The final piece of the puzzle in this evolution may be a technological one. We need new digital tools built for a subculture-centric world. The first era of internet platforms was revolutionary. They enabled small creators to build monetized platforms and streamlined content discovery. But these platforms were also built to reward scale, where content should be optimized for short-form and creator rewards are distributed based on vanity metrics like clicks and views. While niche communities can now easily get off the ground, maintaining these communities is still largely unsustainable. A clear tension here comes to a head. There is a lack of alignment between the platforms built for a culture from a decade ago and the flourishing subcultures that exist today.

I don’t think it’s reasonable to tell everyone to retreat from the internet in protest. The internet gave us powerful tools for connection, and we should leverage them. But the next era of internet platforms must be natively built to serve the needs of smaller communities, enabling them to be sustainable but not necessarily scale. Only through that transformation do I think we’ll be able to completely enter a new era of internet-native creativity and culture.

thank you to Santi, Nabeel, Sean, and Andy for your thoughtful notes and feedback

Books that highly informed my thoughts on this post:

Status and Culture by W. David Marx

Rap Capital by Joe Coscarelli

Internet for the People by Ben Tarnoff