Ryuichi Sakamoto: Coda (2017)

I wrote a year ago about taste and how it’s been outsourced to feeds and algorithms. It was an honest effort, but it barely grazed the surface of what has become a personal obsession: what drives taste and creation?

I recently watched a collection of documentaries about artists I deeply admire:

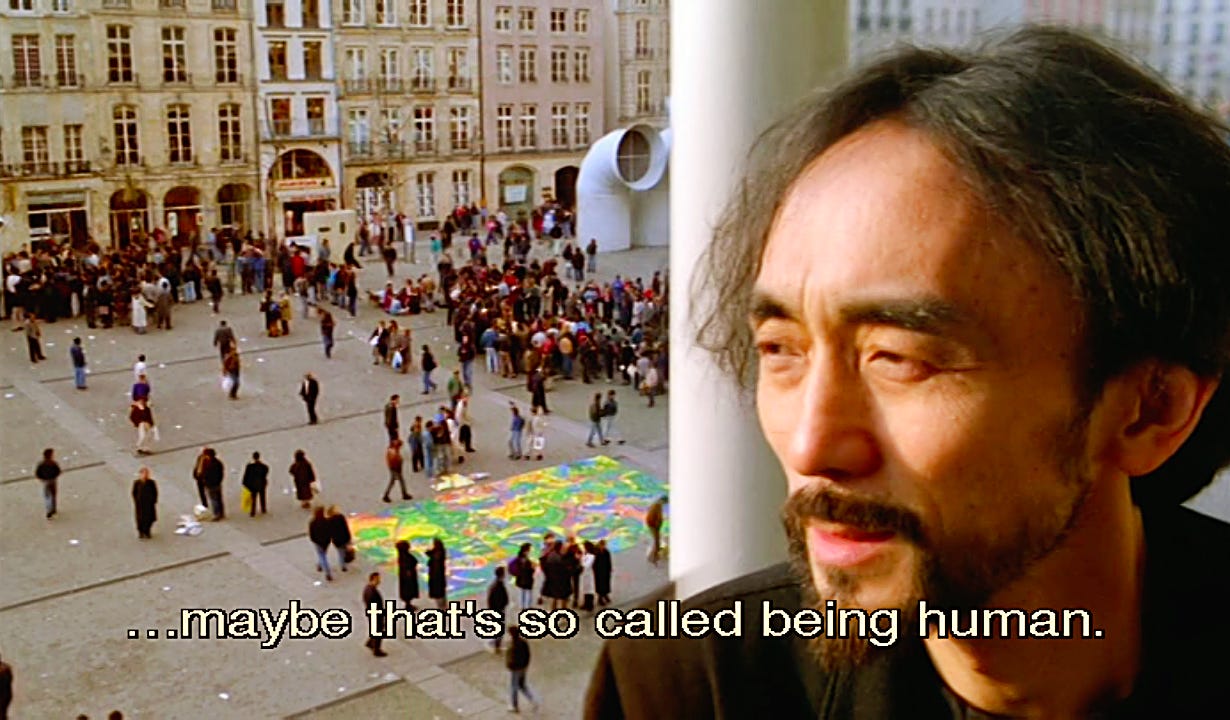

Ryuichi Sakamoto: Coda (2017)

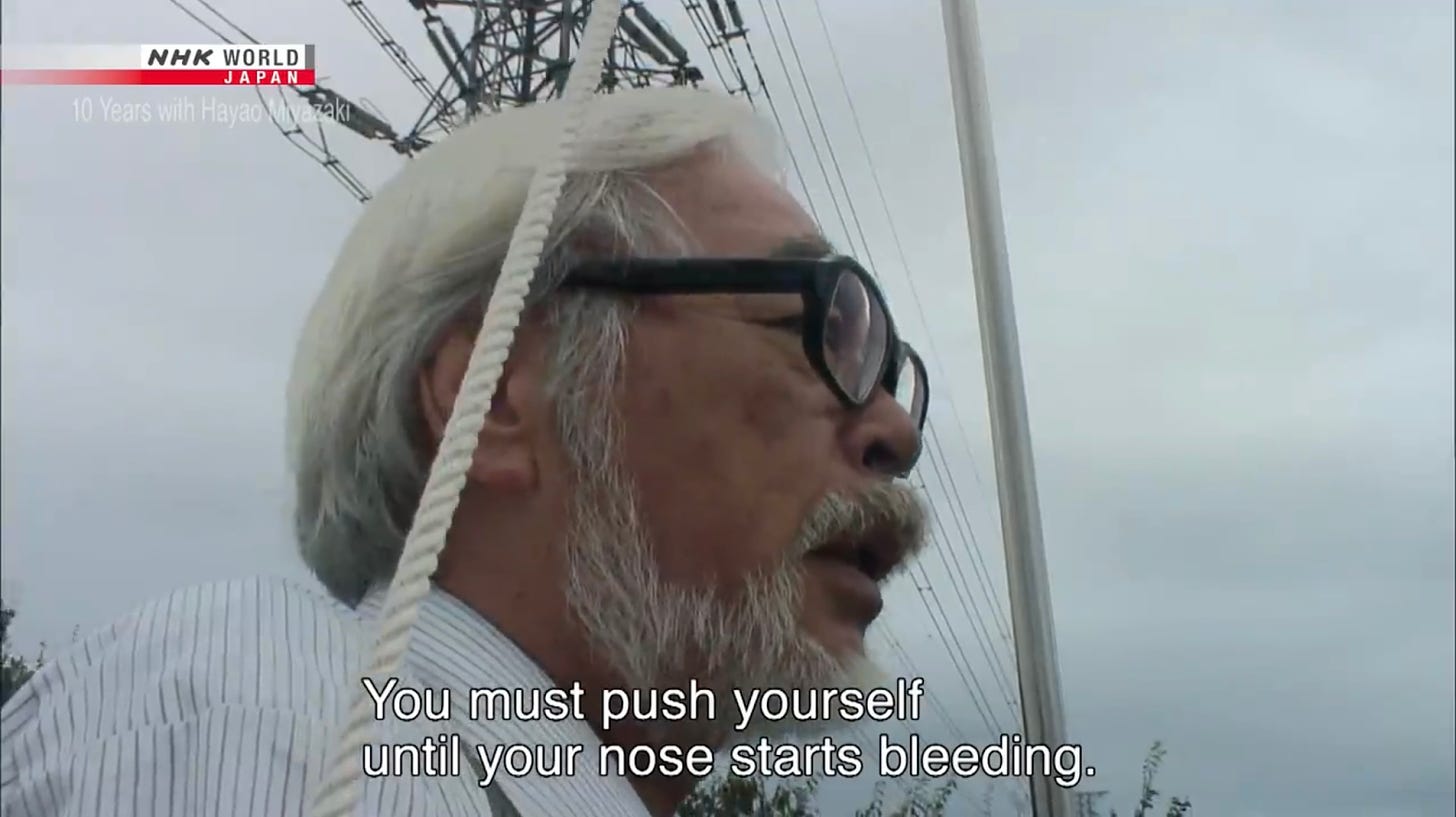

The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness (2013) (on Hayao Miyazaki)

Notebook on Cities and Clothes (1989) (on Yohji Yamamoto)

Choosing these artists was purposeful. I was curious to see how their artistic processes might compare given they share culture and era, but span different mediums: music, film & animation, fashion.

I learned that Sakamoto, Miyazaki and Yamamoto are idiosyncratic characters, as artists often are. Sakamoto is reverent and hopeful, while Miyazaki rather flippant and dry, and Yamamoto exudes cool, withdrawn Parisian (where he splits his time with Tokyo).

I gathered a few actionable notes: pay close attention to your surroundings, create with whatever you have around you. But the more compelling truth I discovered was that these artists create from unwavering first principles.

Yamamoto: material and texture first, form second

Miyazaki: animation must be grounded in realism

Sakamoto: everything is music, everything returns to nature

Core beliefs are the kernels of taste. Once you become aware of an artist’s personal truths, you begin to see them everywhere in their body of work. Art hinges on these beliefs, subtly manifesting like hidden signatures.

Therein lies the inextricable tie between creation and taste.

Creation is an outward expression of your inner world, while taste is the interplay of ideas, beliefs, and convictions from which that world emerges.

Taste guides creation and in response, creation informs taste.

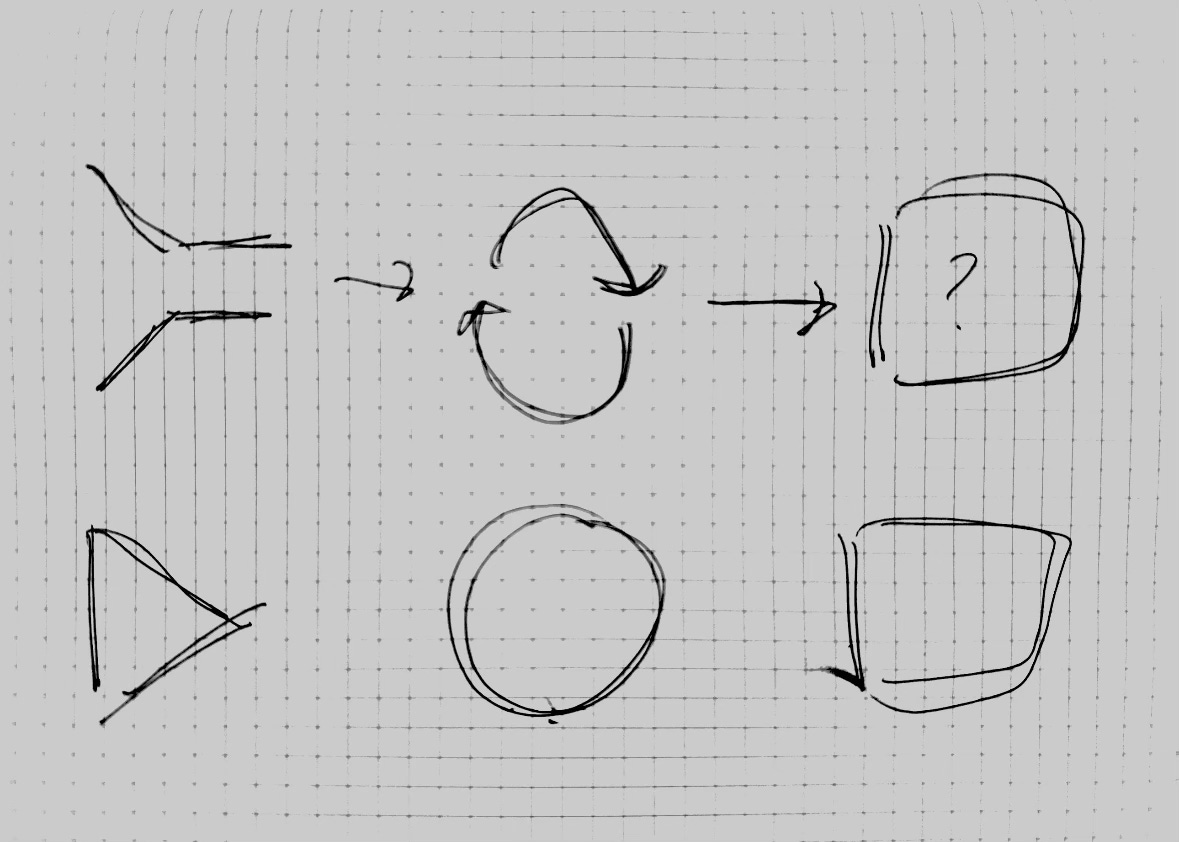

I drew my own rough visual framework for how I think about the act of creation.

Beginning from the left, you first gather inputs, references, sources.

To quote my friend Ruby who has also written about taste (and is one of the most thoughtful and tasteful people I know):

“Turn off the computer. Go live in the world of objects. Go to the stores in your city or town. Touch things. Try them on. Sit on them. Peer, leer, jeer!”

Then you must synthesize your findings; develop an intimate understanding of why certain objects resonate with you. Explore, ask questions, sit in wonder, and repeat, until you can uncover patterns and build frameworks around your findings.

Next, create! The external manifestation of the world-building you’ve done internally.

Consume → Synthesize → Create

Though simple, this framework unlocked a lot for me. Visualizing this process helps me break down how I spend my time. This structure draws the relationship between taste and creation more explicitly, allowing me to better attempt to answer key questions: Is taste objective? Are accessible creator tools net beneficial or harmful?

Consumption looks wildly different today than it did ten years ago. This is not a unique insight, people have been grappling with the consequences for years. At first, the protest was that there’s too much media to consume. Now, we’re tumbling headfirst towards media that is algorithmic and hyperpersonal. If there’s too much to consume, make sure people are efficiently served the “right” content. We’re even beginning to entertain a world in which people watch their own individualized versions of films (in my own words, hell).

Most people stop at consumption. This has always been the case, and will continue to be the case forever and ever, Amen. This makes sense, as it requires the least amount of effort. But the evolution of algorithmic and hyperpersonal content makes moving beyond consumption even more challenging. If I already enjoy the content I’m being served, why would I spend time in discovery or discernment (synthesis)? However, there is a critical, existential issue embedded here.

Synthesis is where taste develops.

From Tyler, the Creator:

“We’re at a time where things don’t hold personal value anymore, it’s now for other people. Even a conversation about music now has changed. People just say something’s ‘mid’ but they can’t articulate why they don’t like it. They don’t have the vocabulary or the energy or the actual care. People don’t even talk about why they like the shit they actually like.”

I wrote about this last year, so I won’t cover it much further, but I want to turn to how these trends impact the act of creation and the creator class. Today’s creators operate within the paradigms of two technological shifts:

Mass, personalized media consumption

Accessible creator tools

We addressed the first, now onto the second.

Modern tools make the creative act easier, period.

Take long form writing. Many contemporary writers I admire cite blogging as the start of their career. Bloggers in the early 2000s had to master a new, foreign medium. But they were willing to master the medium because they absolutely loved writing. I doubt that this is the case for the majority of online writers today. After all, I can create a new personal blog/newsletter/website and monetize it in less than ten minutes. If creating a newsletter was even 50% harder, I doubt I would even have a Substack today. This is not an argument against the democratization of creative tools.

Open tooling is essential.

Art is gatekept, helmed by legacy institutions and deep-pocketed kingmakers. Meryl Streep’s famous monologue from the 2006 film The Devil Wears Prada sums it up well:

“...that blue represents millions of dollars and countless jobs, and it's sort of comical how you think you made a choice that exempts you from the fashion industry when, in fact, you're wearing a sweater that was selected for you by the people in this room from a ‘pile of stuff.’"

Accessible tooling and open media attempt to level this wildly uneven plane by giving young, diverse audiences and artists unprecedented power.

I’m reminded of Nam June Paik who pioneered the genre of video art by repurposing prohibitively expensive equipment to make it more affordable for himself and other artists. Or J Dilla’s innovative approach to sampling and hardware which inspired his contemporaries to approach music production in the same minimal manner.

Beyond medium (tools, platforms), a creator must also master message.

Message sits at the heart of all creation. Message is meaning and belief.

Sakamoto, Miyazaki, and Yamamoto are artists who have distinct, decisive beliefs about the world. To create is to fiercely challenge these beliefs—to poke, prod, test them.

This is why taste is essential. This is not to say that taste is objective or static. Taste is intensely personal and constantly evolving. It is not the result of conviction in a single idea, but of the firm belief that you have a perspective on the world that must be shared. And as you engage in the creative act, your inner world reverberates loudly, leaving an indelible mark on the world itself.

Taste is the foundation of creation. Without it, you’re left a prisoner of imitation.

Fashion is an excellent example of teasing out style that is imitative versus style that has personal taste.

Yohji Yamamoto (narrated by Wim Wenders) on style:

"Style can become a prison. A hall of mirrors in which you can only reflect and imitate yourself. Yohji knew this problem well. Of course, he had fallen into that trap. He had escaped from it, he said, the moment he had learnt to accept his own style. Suddenly, the prison had opened up to great freedom, he said. 'That for me is an author. Someone who has something to say in the first place, who then knows how to express himself with his own voice, and who can finally find the strength in himself to become the guardian of his prison, and not to stay its prisoner.'"

A more contemporary note from fashion writer Rachel Tashjian Wise:

A response from fashion writer Brenda Weischer.

In drafts of this piece, I referred to the process of creation as “the creative arena,” which confused initial reviewers. “Why would you use such a combative term?”

This was intentional. I wanted to stress that the creative act can be acutely painful. The arena has glorious lore. It’s violent, spectacular, thrilling. It’s also deeply mythical, social, dynamic.

To create—to enter the creative arena—is to pursue the divine. And to emerge from it, one must be armed with deep-seated belief.

From Nick Cave:

“What makes a great song great is not its close resemblance to a recognizable work. Writing a good song is not mimicry, or replication, or pastiche, it is the opposite. It is an act of self-murder that destroys all one has strived to produce in the past. It is those dangerous, heart-stopping departures that catapult the artist beyond the limits of what he or she recognises as their known self. This is part of the authentic creative struggle that precedes the invention of a unique lyric of actual value; it is the breathless confrontation with one’s vulnerability, one’s perilousness, one’s smallness, pitted against a sense of sudden shocking discovery; it is the redemptive artistic act that stirs the heart of the listener, where the listener recognizes in the inner workings of the song their own blood, their own struggle, their own suffering.”

Medium was historically a determining factor in the arena; if you were willing to master the medium, you’ve already demonstrated high conviction. New tools make this less relevant. Of course, new mediums are accompanied by new challenges but the matter remains that the arena is constantly transforming before our eyes.

Like taste, creation is deeply personal. Maybe the creative process doesn’t look like an arena at all, but a maze of curiosity or a contemplative daydream. Understanding the shape, surfaces, crevices, and boundaries of your own creative arena is crucial.

What does the creative act look like for you?

If consumption is a firehose, how will you refine your own taste?

What vectors challenge you to iterate, to reflect, to grow beyond medium?

No tool or platform can give you these answers.

This shouldn’t discourage people from becoming creators, not at all. But as execution becomes easier, conviction becomes even more vital. To create is to confront the fundamental question:

What are you willing to do to put your ideas out in the world?

See you in the arena.

thank you to Sean, Ruby, and Nikhil for your thoughtful notes, feedback, and inspiration

References (in order of appearance):

Ryuichi Sakamoto: Coda (2017)

The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness (2013)

Notebooks on Cities and Clothes (1989)

All Star Series: Tyler Talk, Paris (2022)

The Devil Wears Prada (2006)

Nam June Paik: Moon Is The Oldest Tv (2023)

Dilla Time: The Life and Afterlife of J Dilla, the Hip-Hop Producer Who Reinvented Rhythm (2022)