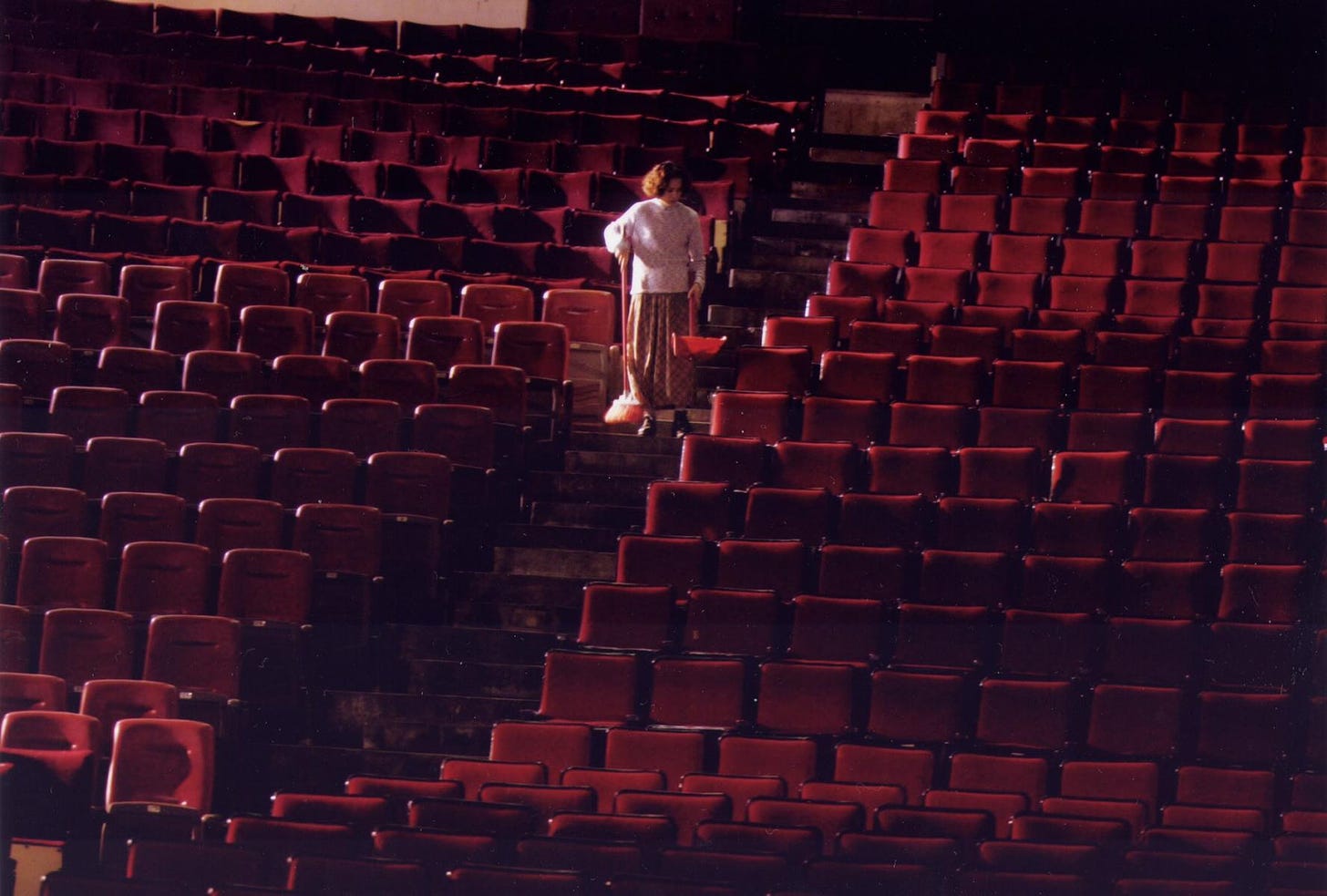

Tsai Ming-liang, Goodbye, Dragon Inn (2003)

From the moment you step into the American education system, you are placed on a 13-year trajectory with a single directive: survive and get into college.

When you reach the end of the ride, you are promptly swept onto another one, shorter, just four years, but infinitely more complex. Possible goals begin to splinter; the clarity of youth begins to blur. Still, most keep their eyes on the same target: pick a career, secure a job.

Fresh-faced and stumbling off the 17-year path set forth from the moment I was born, I arrived in New York, eager to begin the life I had prepared my entire childhood for.

Three months later, I quit my first job. It mercilessly dawned on me that the next 20 years of my life would look nothing like the last.

In a totally casual and chill panic, I asked my infinitely older, wiser, wealthier friends (mostly 27, 28, 29 year olds) when they had begun to actually feel like an adult or at least like their prefrontal cortex had fully formed.

They’d raise an eyebrow, glance upward as if watching their lives rewind in cartoon thought bubbles. After a beat of halfhearted introspection—and maybe a sip of a strong cocktail—they’d throw out “26” like it was an inside joke with time.

While most of my friends thought the question was simply fun dinner fodder, I quietly took their answers to heart, internalizing 26 as the year I would have, maybe not all the answers, but at least a clear trajectory for where the rest of my life would be going. Until then, fuck it, we ball.

26 is now a week away. Four years, four jobs, three relationships, and four apartments later. I’m attempting to tackle the Big Question: Did my prefrontal cortex actually kick in?

Since I first posed the question with the uniquely dramatic fervor of a 21 year old, my feelings towards it have shifted. It’s absurd, of course—who feels their brain rewiring in real-time? But still, it set some vague timeline in place for “getting my life together,” a way to pace myself, to give grace. I set more concrete goals: save up this much, stay at a job for this long, the kinds of benchmarks that made the whole “quarter-life crisis” bit feel a little more grounded.

I’m proud to say I have hit all my paper goals, and weirdly enough: I do think my prefrontal cortex has kicked in.

I instantly knew the moment my prefrontal cortex had kicked in because I was talking to a college student on an existential ramble, and I responded much more apathetically than I would have even a year prior—that is to say, a well-intentioned eye roll and an exasperated “please calm down.”

When you’re 21, every decision feels life-altering, like you are scrutinizing every single thread to make up the core fabric of your life. Over time, these decisions begin to narrow. Time and circumstance are obvious factors, but your own personal preferences also begin to harden. Your center pole takes shape. I’ve found, over the past year especially, that making decisions is much easier—partly because I have much stronger inclinations, but also because I acknowledge that circumstances will always change and so each decision feels much less daunting (and also because psychedelics!).

I’ve written about this before and will quote an older, wiser 36 year old here:

“This is something I still grapple with, and you’ll continue to grapple with it for the rest of your life. What begins to soften the unrest is that you will accumulate so many examples in your life of things that only happened because of timing, both good and bad. And you’ll learn to appreciate them.”

When I started to notice my own gut appear (emotionally speaking, lol), I was thrilled. New skill unlocked. But I quickly found that there was a catch. When your core seems rather solid and decisions much more minor, moments feel much less consequential, much less memorable.

Everything is different, but also strangely the same. I am always changing, but also somehow unmoving.

Moments slip by more quietly now, leaving fewer marks behind. They’re harder to notice, harder to define, slipping through before they fully take shape. Changes creep in slowly and meaning feels just out of reach, like trying to catch smoke. Months later you notice you’re an entirely different person—and you have no idea exactly when or how it happened.

In another totally casual and chill panic, I once again turned towards much older, wiser friends (this time, 30s, 40s, 50s). Luckily for me, they responded with much more empathy than I did to that college student. I asked if they ever noticed their memories slip by and how to hold onto them, how they clock and respond to change.

An (paraphrased) answer from Andy: “Maybe noticing that a change took place at all is more important than knowing what exactly was at the beginning or end of it.”

Nick’s response revolved around watching his toddlers grow up and experiencing the journey all over again, though from a very different perspective—and knowing that’s all that really matters.

As for Eugene, we talked about prolonged adolescence—the societal state of adults wanting to remain children as long as possible.

While this post was originally centered around asking whether my prefrontal cortex developed, I’m not quite sure anymore that that is the question that actually matters.

When I talk to Nick nowadays, there’s always a part of the conversation that goes something like this:

Me: “Listen to this silly thing I heard a younger person complaining about, please tell me I wasn’t like that when you first met me [21].”

Nick: “I mean, yeah, you kind of were.”

I think a lot of growing up, particularly during the internet age, comes with an implicit individual pressure to accumulate, retain, and iterate upon knowledge, both about the world and about yourself.

When I talk to Nick and Andy about how they remember their early adulthoods, they both admit they don’t remember much with precision. But they can see glimpses of themselves in the younger people around them, as if looking through a time-lapsed mirror. Sometimes, in those reflections, a piece of the past clicks back into place.

For most of my life thus far, my goal above all else has always been to rush towards adulthood, that life begins when I reach some level of all-knowing self-assuredness. I think, now, I realize how limited and imperfect the individual mind is. Growth is not an individual journey, not as simple as accumulating memories and searing them to mind. We exist as nodes in a shared web of connections. As experiences circulate between us, we recognize ourselves in others. Collective memories reshape our perspectives and inform our paths forward.

“Self-actualization” or whatever is a worthwhile goal, but I’m beginning to wonder if it’s a misguided one. As the years pass, the slope of change begins to level out, and time, along with its memories, slips through our grasp. To cling to those memories in hopes of extracting some metaphysical insight feels futile—an attempt to hold onto something that’s already dissolving into the past.

a lot of people I could thank here, but I’ll settle for Nick, Andy, Eugene, Jacky, Mathu, and Vivian